SPOILERS FOR 13 REASONS WHY ABOUND!

The controversies surrounding 13 Reasons Why have been numerous and well-enumerated; critics claim that the show glorifies teen suicide by presenting it as a suitable revenge for bullying, that portraying teen suicide at all (especially using attractive young actors) is irresponsible, and that Hannah’s rape scene is triggering for victims. But arguably the biggest point of contention is Hannah’s suicide scene, which is incredibly disturbing. It’s one thing to hear about a child slitting their wrists, it’s another thing altogether to see it happen in graphic detail.

But does the graphic nature of the scene automatically make it irresponsible? I’m not a mental health professional, so I can’t comment about whether the show is responsible about suicide on the whole. But in regards to this particular scene, I tend to agree with 13 Reasons Why writer (and suicide attempt survivor) Nic Sheff, who wrote in Vanity Fair that they included as much detail about the act of suicide as possible in order to shatter the “myth and mystique” surrounding suicide, and especially to “dispel the myth of the quiet drifting off.” For those who are worried that the show “glamorizes” suicide, if nothing else, that scene definitely showed viewers that there is nothing glamorous–or peaceful–about the act itself.

That being said, I agree that the show oversimplifies the motives behind suicide, which are often unknowable, rarely external, and never simple. But while 13 Reasons Why may fall short as a work of art about suicide, it does a fantastic job exploring and exposing a different social ill: rape culture. And in that context, the graphic depiction of Hannah’s rape and suicide were not only understandable, but necessary. It was the fitting end to Hannah’s story, in which she sought to seize control over her own life after that control was taken away from her time and time again.

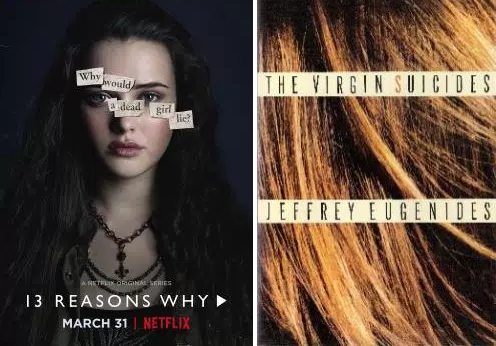

I would argue that 13 Reasons Why is essentially a less literary, but more feminist version of the Jeffrey Eugenides novel, The Virgin Suicides. In both works, the suicidal act itself is an inevitability, a known fact, which allows the pall of death to hang over all of the proceedings, and make the systematic mistreatment of the young girls take on new significance. But where one portrays suicide as an unknowable mystery, the other portrays it as an entirely preventable social ill. Where one explores rape culture through the lens of the male gaze, the other sees the female protagonist very explicitly take back her own narrative from those who victimized her.

When I first read The Virgin Suicides, I thought it was a brilliant indictment of society’s objectification of women. The novel explores the suicides of the Lisbon sisters–five beautiful white blonde girls whose mysterious malaise captivates their suburban Michigan neighborhood. While we know from the beginning that they will all kill themselves by the end of the story, the novel follows the time leading up to their untimely demises, filtered by the perspective of the collective neighborhood boys–using an amorphous second person plural narrator.

It doesn’t get much more male gaze-y than that, and that’s very much the point. The Lisbon girls, particularly the main character Lux, are the victims of all manner of gendered mistreatment. When Lux falls for a boy at school, they have sex after a school dance, and the boy promptly abandons her in a soccer field without a ride home, with no explanation besides, “I just got sick of her right then.” When the girls are subsequently late for their curfew, their evangelical parents lock them in the house for months on end. In retaliation, 16-year-old Lux has sex on the house’s rooftop with multiple older men, who are presumably committing statutory rape.

And while the boys that form the Greek chorus seem to decry the girls’ sexual objectification, the implied author is equally intent on lampooning romantic objectification. The boys convince themselves that they “love” the Lisbon girls, and yet they clearly don’t know anything substantive about them. Lux is the only one who even makes an individual impression as a character, and for most of the novel, she’s simply a mish-mash of stereotypes about Lolita-esque child vixens; the boys refer to her as a “succubus” and genuinely believe that she has a deep, mysterious understanding of sex and therefore a relationship with death. They claim to care about the girls, and yet they miss plenty of opportunities to help the girls because they are too wrapped up in their own fantasies.

We went over their last months in school, coming up with new recollections. Lux had forgotten her math book one day and had to share with Tom Faheem. In the margin, she had written, “I want to get out of here.” How far did that wish extend? Thinking back, we decided the girls had been trying to talk to us all along, to elicit our help, but we’d been too infatuated to listen.

Interestingly (and somewhat problematically), neither The Virgin Suicides nor 13 Reasons Why presents suicide as a byproduct of mental illness; rather, they both focus on the intersection of suicide with social ills that make such a desperate act seem like a the only option. Like Lux, the 13 Reasons Why protagonist, Hannah, has been subjected to years of objectification, abuse, and even-more-explicit slut-shaming. A boy she liked took an upskirt photo of her and shared it with his friends, her classmates tortured her after she appeared on a list as the grade’s “Best Ass,” she witnessed her unconscious friend being raped, and then she was raped herself, and gaslit by the only adult she trusted enough to tell. And like Lux, she shows no signs of being clinically depressed, which makes the suicide seem all that much more preventable. These works are not about the potentially deadly nature of mental illness, but the potentially deadly nature of being a teenage girl in a patriarchal society.

And it was then Cecilia gave orally what was to be her only form of suicide note, and a useless one at that, because she was going to live:

“Obviously, Doctor,” she said, “you’ve never been a thirteen-year-old girl.”

And like The Virgin Suicides, 13 Reasons Why is filtered through the perspective of an adolescent male who is infatuated with Hannah. And like Eugenides’ narrators, Clay allows his feelings for Hannah to obscure her obvious cries for help. While we can hardly fault him for it, if Clay hadn’t been so emotionally involved in the outcome of his encounter with Hannah, he might have intuited that her pain is much bigger than him. We can fault him a little more for slut-shaming Hannah after the upskirt photo incident, and for reducing her to a manic pixie dream girl (at least a little bit). He was convinced he was in love with her, but, as he learns the hard way when he receives the tapes, he barely knows anything about her.

Eugenides writes in Virgin Suicides, when the boys are lucky enough to take the Lisbon girls to a school dance and make out with them a little bit:

Even though he tasted mysterious depths in Bonnie’s mouth, he didn’t search them out because he didn’t want her to stop kissing him.

Clay is well-meaning and very likable–far more likable than the budding Peeping Toms of Virgin Suicides–which makes his complicity in the rape culture swirling around Hannah harder to swallow. But from a feminist perspective, his relative moral innocence makes the underlying message all the more meaningful: it reinforces that rape culture makes virtually all men unwitting co-conspirators to varying degrees, even the most adorable ones.

The Virgin Suicides gives essentially the most feminist presentation of the male gaze; similar to classic works like Lolita, it presents the female characters as a series of contradictory feminine ideals in order to critique and deconstruct the same male gaze that it’s trafficking in. While Lux appears to be a nymphet-like sex goddess upon superficial reading, Eugenides makes it very clear that the narrators are extremely unreliable. For example, while the boys are convinced that Lux has an instinctual understanding of sex, which she uses to gain power over men, and Eugenides makes it clear in at least one passage that her hypersexed behavior seems like “playacting,” and that she doesn’t even seem to enjoy sex very much.

Lifting their heads from the soft shelf of Lux’s neck, they found her eyes open, her brow knitted in thought; or at the height of passion they felt her pick a pimple on their backs. Nevertheless, on the roof, Lux reportedly said pleading things like, “Put it in. Just for a minute. It’ll make us feel close.” Other times she treated the act like some small chore, positioning the boys, undoing zippers and buckles with the weariness of a checkout girl.

The Virgin Suicides successfully spits on the idea that these boys are capable of “rescuing” the Lisbon girls from forces much bigger than themselves–and paints the girls as morally ambiguous figures in the process. While the boys are ready and waiting to be the girls’ white knights, they haven’t even taken the time to learn what the girls need to be saved from. As a result, the girls take back their own narrative from their admirers by following the script of the damsels in distress–playing records over the phone, calling the boys over to run away and ride off into the sunset–only to kill themselves with the boys in the house. Not only do Bonnie and Therese wait until the boys are in the house (distracted by the tantalizing possibility of romantic contact with Lux) to commit suicide, but Lux waits until they have left in horror, so they will have to live with the fact that they might have been able to save her. They very explicitly–and somewhat cruelly–punish the boys not only for romantically objectifying them, but for arrogantly thinking that they could be saved.

“We had never known her,” the boys think to themselves when they find Bonnie dead. “They had brought us here to find that out.”

At first blush, 13 Reasons Why seems quite similar; Hannah is undoubtedly sympathetic, but is also portrayed as cruel and petty. She outs Courtney on the tapes because Courtney wouldn’t be her friend, she tortures Clay by putting him on the tapes when she never had any intention of blaming him, and she reveals Jessica’s rape to twelve other students when she never revealed it to Jessica while she was alive. As in Virgin Suicides, these actions are effectively depicted as Hannah’s desperate reaction to her own suffering, but still prevent the audience from sanctifying her. Unlike Clay and Eugenides’ narrators, we don’t have the luxury of seeing these young women as pure, “virginal” angels, but rather are encouraged to see them as complex–and often unlikable–human beings.

But dissimilar to Virgin Suicides, Hannah’s life isn’t filtered entirely through Clay’s eyes. The show’s format is a mixture of his memories and her narration, but she is undeniably the star. She is the unreliable narrator who has the privilege to remember her own life incorrectly, in the ways that suit her. Funnily enough, one of the most potentially insensitive parts of the series–the notion that she is getting “revenge” on her bullies by committing suicide–solidifies the show as a decidedly feminist work. Unlike the Lisbon girls, who try desperately to take back their narrative but are still, to us, little more than figments of young boys’ fevered daydreams, Hannah quite literally takes back her story with a vengeance. Case in point: in a book that is all about their suicides, the Lisbon girls all die “offscreen,” while Hannah dies painfully and graphically before our eyes.

While the show is technically written from Clay’s perspective, any doubt that Hannah is the true narrator of the story evaporates with that controversial depiction of her suicide. Up to that point, one could argue that Clay was visualizing Hannah’s tapes, taking her narrative and filtering it through his memories of Hannah. But not only does the suicide scene, by definition, takes place after the tapes are over, but it is so viscerally and disturbingly detailed, there is no doubt in the viewer’s mind that it is a reliable flashback. The Lisbon girls reenacted their lack of personhood in life by allowing the boys to look away from their deaths; while, for better and for worse, Hannah won’t let us look away.

The Virgin Suicides is, in many ways, much more insightful about the act of suicide, because the Lisbon girls’ desperate act is portrayed as, on some level, ineffable. While the narrators spend an entire book telling us all of the reasons the girls may have wanted to commit suicide, the only conclusion they truly come to is that they didn’t really know anything about them. They are left sad, bitter middle-aged men who try to divine their reasons for killing themselves by staring at the few decaying objects they salvage from the Lisbon house–make-up, Cecelia’s Converse, Lux’s bra–and imagining a young Lux while they have sex with their partners. They quite literally reduce the Lisbon girls to objects in a vain attempt to know the unknowable, and all the while decry them for being selfish. Our sympathies may be with the girls, but the boys get the last word. They get to define the girls’ deaths in the end, on their own narcissistic terms.

They made us participate in their own madness, because we couldn’t help but retrace their steps, rethink their thoughts, and see that none of them led to us. We couldn’t imagine the emptiness of a creature who put a razor to her wrists and opened her veins, the emptiness and the calm. And we had to smear our muzzles in their last traces, of mud marks on the floor, trunks kicked out from under them, we had to breathe forever the air of the rooms in which they killed themselves. It didn’t matter in the end how old they had been, or that they were girls, but only that we had loved them, and that they hadn’t heard us calling, still do not hear us, up here in the tree house, with our thinning hair and soft bellies, calling them out of those rooms where they went to be alone for all time, alone in suicide, which is deeper than death, and where we will.

Thirteen Reasons Why is not nearly as nuanced as The Virgin Suicides in its understanding of suicide, an inherently senseless act. The tapes tie everything up a little too neatly to be realistic, and since Hannah doesn’t show any of the classic signs of depression, there is very little consideration that she may have killed herself for other, less condensable reasons. The show definitely oversimplifies an extremely complex issue by implying that suicide would be eliminated if we all practiced more empathy and social justice. But, unrealistic as it may be, it is very much Hannah’s story. Where Virgin Suicides demonstrates the deleterious effects of denying a person’s humanity by taking the Lisbon girls’ narratives away from them, 13 Reasons Why actively fights against the male gaze, and allows Hannah to reclaim her own subjectivity and humanity in death.

Insightful article. Thank you for writing it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Virgin Suicides is one of my favourite books and one of the few times that a film adaptation has lived up to the source material. Sidenote though, your final quotation is missing a few words off the end, which (quoting from memory, so I may be paraphrasing) is “…and where we will never find the pieces to put them back together.”

LikeLike