Charlotte Bronte was born on this day in 1816. Today we take a look at Villette, her late undersung masterpiece.

Charlotte Bronte was born on this day in 1816. Today we take a look at Villette, her late undersung masterpiece.

“Her life should always be in harmony with the most pleasing impression she should produce; she would be what she appeared, and she would appear what she was. Sometimes she went so far as to wish that she might find herself some day in a difficult position, so that she should have the pleasure of being as heroic as the occasion demanded.”

Henry James, born on this day in 1843, created the indomitably original female character of Isabel Archer, who, like many of the greatest Victorian heroines, was idealistic to the extent that it was her defining quality, and yet did not have particularly defined ideals. Just as Middlemarch‘s Dorothea was a revolutionary without a revolution, a Theresa who never had the opportunity to manifest her lofty ambitions into independent action, Isabel Archer was a highly moral woman who was never expected to develop any specific morals, an idealist without any ideals.

Why did the morning rise to breakSo great, so pure a spell,And scorch with fire the tranquil cheekWhere your cool radiance fell?

Poetry so often conflates springtime with rebirth, renaissance, hope, and the like, but Emily Brontë’s work begs to differ. The narrator of “Ah! Why, Because the Dazzling Sun” spends the poem shutting her eyes tightly (and vainly) against the “blood-red” light that “throbs with her heart” and destroys her peace. And as she says in “Fall, leaves, fall”:

I shall smile when wreaths of snowBlossom where the rose should grow;I shall sing when night’s decayUshers in a drearier day.

Brontë’s poetry seems keenly aware of the Icarus myth: her relationship to daylight and springtime springs from an understanding that sunlight is not the product of a benign reflection, a consumptive fire.

From “Ah! Why, Because the Dazzling Sun” again:

O Stars and Dreams and Gentle Night;O Night and Stars return!And hide me from the hostile lightThat does not warm, but burn—

A commotion at the door. It is Christophe. He cannot enter in the ordinary way; he treats doors as his foe.

When it became de rigueur a few years back for every book club to sweat over the first two installments of Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall trilogy and its dense prose about Thomas Cromwell and Henry VIII, I had no interest in joining the crowd. (This was mostly due to a general lack of interest in history about which I should probably feel more guilty than I, in fact, do.) But an article in the NYRB excerpting Hilary Mantel’s directions to the actors in the stage adaptation changed my mind.

You have the face that suits a womanFor her soul’s screen —The sort of beauty that’s called humanIn hell, Faustine.

“…the transmigration of a single soul, doomed as though by accident from the first to all evil and no good, through many ages and forms, but clad always in the same type of fleshly beauty.”

You seem a thing that hinges hold,A love-machineWith clockwork joints of supple gold —No more, Faustine.

A great moment from Jane Austen’s Persuasion:

Immediately surrounding Mrs Musgrove were the little Harvilles, whom she was sedulously guarding from the tyranny of the two children from the Cottage, expressly arrived to amuse them. On one side was a table occupied by some chattering girls, cutting up silk and gold paper; and on the other were tressels and trays, bending under the weight of brawn and cold pies, where riotous boys were holding high revel; the whole completed by a roaring Christmas fire, which seemed determined to be heard, in spite of all the noise of the others. Charles and Mary also came in, of course, during their visit, and Mr Musgrove made a point of paying his respects to Lady Russell, and sat down close to her for ten minutes, talking with a very raised voice, but from the clamour of the children on his knees, generally in vain. It was a fine family-piece.

In noticing what a lovely scene the family makes, the narrator steps back to a frame of observation that parallels ours as readers—admiring the artistry with which the scene was assembled—such that the statement can’t quite be distinguished from Austen reflecting approvingly on herself. It’d be insufferable, of course, if the scene weren’t perfect, but it is, and the flourish sits gently on top: “a fine family-piece.”

So she let her stomach get bigger and bigger, held the selamatan ritual at seven months, and let the baby be born, even though she refused to look at her. She had already given birth to three girls before this and all of them were gorgeous, practically like triplets born one after another. She was bored with babies like that, who according to her were like mannequins in a storefront display, so she didn’t want to see her youngest child, certain she would be no different from her three older sisters. She was wrong, of course, and didn’t yet know how repulsive her youngest truly was.

Eka Kurniawan’s Beauty is a Wound takes place in the Indonesian city Halimunda, where a prostitute named Dewi Ayu lives through many decades of the turbulent twentieth century. It has a giant cast of vibrant, larger-than-life, sometimes-magical characters and a wide tapestry in terms of story and time, and its view of history is startlingly, centrally female. This romp of a book dwells on the crude, from piss and shit to sex, more often than on the sublime — but a New York Times review was rather inadequate when it described Kurniawan’s work as being merely about “unruly, untameable and often unquenchable desires.” Because it’s not just about desire; specifically, it features numerous, terrifyingly varied portrayals of rape. The beauty possessed by Dewi Ayu’s first three daughters, like “mannequins in a storefront display,” is not just a wound but a grave, ever-present danger for each of them.

I read the book as being “postcolonial” in the sense that it does examine the volcanic changes that take place in Javanese society after independence from the Dutch, from Japanese occupation to civil war; its topics range from law enforcement and local politics to the experiences of prisoners of war. But in the relations between male and female characters, the country’s violence and strife is replicated in miniature. So many men see their way clear to raping, to owning, to violating, some other woman. And each female character who is raped suffers as mightily as if she were an entire country unto herself.

It’s a fascinating, sometimes offensive read, and I’m still not sure I understand it fully, nor was I actually sure I enjoyed it. But as a book that has both the grandeur of García Marquez and the mordant scatological humor of Beckett, and is told in its own original, rambunctiously vulgar, yet beautiful voice, it is well worth a read.

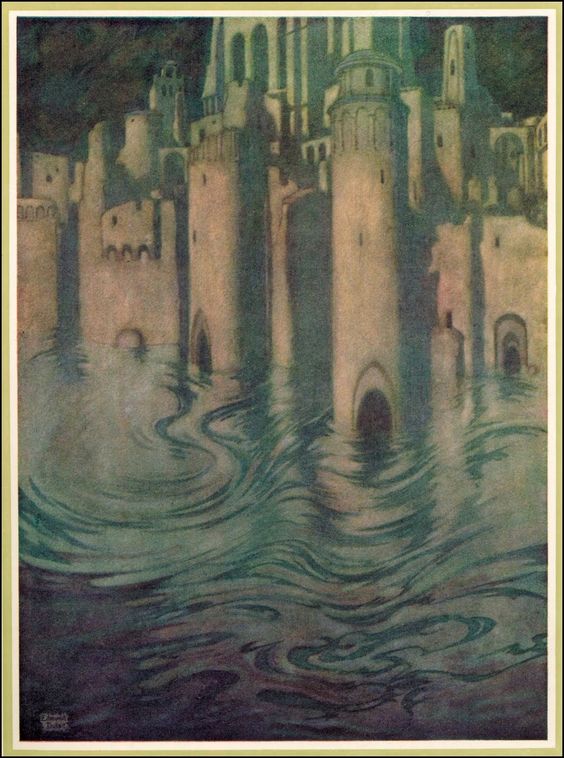

But lo, a stir is in the air!

The wave- there is a movement there!

As if the towers had thrust aside,

In slightly sinking, the dull tide-

As if their tops had feebly given

A void within the filmy Heaven.

Poe’s “City in the Sea” refers to the city erected by Death, in which all lost souls, squandered riches, and fallen idols are laid to waste in “melancholy waters,” as Death looks “gigantically down” in satisfaction.

But these lines also tend to remind me of the metropolis in which kht, jd, and I reside: New York, of course. On its best days, the towering skyline ascends to the heavens and punctures them, sending their contents spilling down onto us. On its worst days:

Hell, rising from a thousand thrones,

Shall do it reverence.

The Razzies have come under fire in recent years for being an opportunistic, publicity-hounding sham that doesn’t add anything new to the conversation, or even manage to be funny. Rather than effectively satirizing “legitimate” award shows like the Oscars, they’ve become known for taking in-poor-taste potshots at easy targets, beating each year’s dead horse until it’s really, really, really dead.

And what’s an easier mark than Fifty Shades of Grey? Both the book series and the 2015 film are embarrassing blemishes on our culture, appallingly sexist and mind-numbingly inane pornos that reinforce damaging stereotypes and actively encourage young women to seek–and try to “save”–abusive partners. So naturally, it received no less than six Razzie nominations, pretty much every single one for which it was eligible. Continue reading →

To be given dominion over another is a hard thing; to wrest dominion over another is a wrong thing; to give dominion of yourself to another is a wicked thing.

Toni Morrison, A Mercy